What a day this was! Three fish over 20″. I fished with my friend, Frank Corrente, and guide Ben Rinker put us over some amazing fish.

What a day this was! Three fish over 20″. I fished with my friend, Frank Corrente, and guide Ben Rinker put us over some amazing fish.

This lovely Atlantic Salmon was taken on a 2019 trip to Cape Breton with my childhood friend, Bob Woods. Hurricane Dorian was bearing down on us, but we managed to squeeze two days of fishing before the storm.

Floated Kellam’s Bridge to Tower Road. This footage was shot just above Tower Road. With Guide Ben Rinker.

I was twelve years old the summer I lost my first big fish. New Jersey’s dog days of August had set in, our hometown creek was low and clear, and the buzzsaw drone of locusts filled the air. I had been fishing down along the lower section of river for most of the morning. When I came to a sharp bend we called “Tommy’s Hole” I spotted a large fish holding in the current toward the bottom of the pool. It was a big Brown, perhaps eighteen or nineteen inches and substantially larger than anything I had ever before seen in this small creek. The far side of the pool bend formed a high bank, and I crossed upstream to the opposite side to have a better shot at the fish. I tied on almost every fly in my box, but to no avail. The trout wanted nothing to do with me, and eventually moved out of sight. For the next two weeks I haunted that bend, but he managed to stay concealed. I daydreamed of coming tight on him, and the picture my mom would take of me that I could show all my fishing bud’s.

After a rainy deluge, three weeks later, I returned to the scene of that first sighting. This time I fished from the other side of the creek, on the high bank. The river was still high and coffee-colored from the rains, and instead of the flies in my fly box, I strung on a long night crawler I had gathered from my wet front lawn the night before. I chucked the worm upstream without weight and let it drift into where I had seen the fish holding. It didn’t take long – suddenly my line was alive with the distinctive tap-tap and I was tight to the biggest trout I had ever hooked. I managed to horse him up to the cliff, and began to try to haul him up the bank. He was halfway up when the hook pulled out and I watched he and my fish picture agonizingly, slowly slide back down the bank and disappear into the rain-swollen water. It was like a blow to my solar plexus. To this day I can still viscerally remember the bitter disappointment and picture the big, brown spots that freckled his flanks. I really wanted that picture.

It is hard to believe that event happened sixty years ago, and is still so fresh in my mind. Since then, there have been some great fish pictures, and many more that big, crafty old fish relieved me from the privilege of owning.

But about a decade ago, my relationship with fish and pictures became much more complicated. Until then, pictures seemed to be an afterthought – an occasional shot of a nice fish at most. But then, suddenly, there were digital cameras, iPhones and GoPros, and poof, every fisherman was also a professional photographer. Profusions of new trout magazines are filled with “hero shots” touting the pursuit of quality, trophy fish, not only from local rivers, but more and more from exotic fisheries worldwide. Fishing had become an extreme sport. And I drank the cool aid.

Suddenly, the most important piece of equipment wasn’t my waders, boots, rod or fly box – it was my camera. Eventually, fighting a fish became a means to an end – and that end wasn’t the pure enjoyment of the moment – it was the picture. Now I am spending more time at home editing my shots and posting my pictures. If I catch no fish I am chagrinned. If I lose a good fish, I am inconsolable. A sense of greed slowly takes over. Suddenly, a beautiful 12” or 14” trout becomes simply a disappointment. My longtime Delaware River guide and friend, Ben Rinker, sighs and obligingly clicks away with my iPhone or camera, all the while wishing he can get the lovely, tired Brown I was clumsily holding back into the water as quickly as possible. At the fly shop where I work, I won’t miss a chance to whip out my iPhone and share some fish porn. And so it is.

Recently, I took a trip to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia with my wife, Debbie, to celebrate our 30th wedding anniversary. We whale watched, hunted for fossils, walked along the stony beaches, hiked along the wooded trails in Cape Breton’s amazing National Park, and ate ourselves silly. And, since Cape Breton has some exquisite, world-class salmon rivers, of course I booked two days with a wonderful guide, Robert Chiasson, to fish the lovely Margaree River. Having had four prior Atlantic Salmon trips, all of which produced a total of one grilse, I was seriously in quest of that ultimate hero shot – me holding that huge, bright silver fish – that would give me the creds back home.

The first day was ugly. Driving rain – twenty hours of it – had swollen and colored the lower river, and we were forced to hunt the upper sections. Rain pelted us along with thirty-five mile per hour winds. My salmon fishing karma continued.

But the second day dawned calm and overcast, and the lower river had cleared enough to fish. We fished the Dollar Pool, beautiful and long enough for three fishermen to fish at a time. I was on my third pass in the lower pool when the water exploded behind my fly and the line came tight. In an instant, I had a shot at my ultimate picture. I tried not to hurry or to force the salmon, as I would gain line then lose it back to the fish. Little by little I was able to work the fish in closer, only to hear the drag buzz again as the fish bolted away. Finally, after about ten minutes, I had the fish close to the bank. As Robert waded out and reached down to tail the fish, the fish suddenly bolted. I was tight on him and in an instant, the eight-pound tippet parted. The fish was gone.

Robbed in the last second of my hero shot. The shot that, in my mind, I was already showing to the folks at the fly shop, and that would have been the icing on the cake for our vacation. Try as I might, I could not shake that moment. A thousand “what ifs” spun around and around in my mind.

Later that evening, back in the chalet room with my wife, still bitterly disappointed, I halfheartedly surfed Facebook, scrolling through the political rants, cat shots and fish pictures, I came upon this post from an old acquaintance:

“I know that some of you have been wondering where I’ve been for the past month as I have not been on Facebook. I thought I would share with you now that I have been absent due to some medical issues that we have been seeking answers for. I now have them, and it seems that the mass that the doctors initially thought was benign is not. And that the cancer has spread to my liver and pancreas. There is a procedure that can be done that will offer hope; a 10% chance of cure, but more likely an extension of life of several years. That is ok with me, and I am resolute to do whatever is possible to fight this. I will also have to undergo chemo and radiation, so we can all laugh together when my hair falls out. My wife and family are all with me and are my support mechanism. I ask for your prayers and offer my deepest thanks for your ongoing support. I’ll keep you posted as time goes on.”

Two weeks have gone by since I read that post, and I am back home in Connecticut as I write this. There is an enormity to this life that lifts us up like a ferocious ocean wave and twirls us around helpless in the undertow. Sometimes it is too big to escape, too deep to find bottom, and too strong to fight. But like the Ghost Of Christmas Future in Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” it always points us to what’s really important.

Earlier today at the fly shop, I found myself telling my cohorts about my salmon encounter. The amazing fight, the congenial support from the resident pros, how the bright fish flashed copper in the peat-stained water. And that one of the Margaree regulars had an iPhone, and, unknown to me, took pictures of the fight. And looking at them now, they seem to be what I should be looking at – those delicious minutes that wild fish and I were joined by that fragile length of leader when I could feel every head-shake, thrill to every jump, and feel the brute strength of those withering rushes – the real reason we do what we do. Early in “A Christmas Carol,” the ghost of Jacob Marley tells Scrooge, “…I wear the chain I forged in life.” A chain that, perhaps, looks surprisingly like a hero shot.

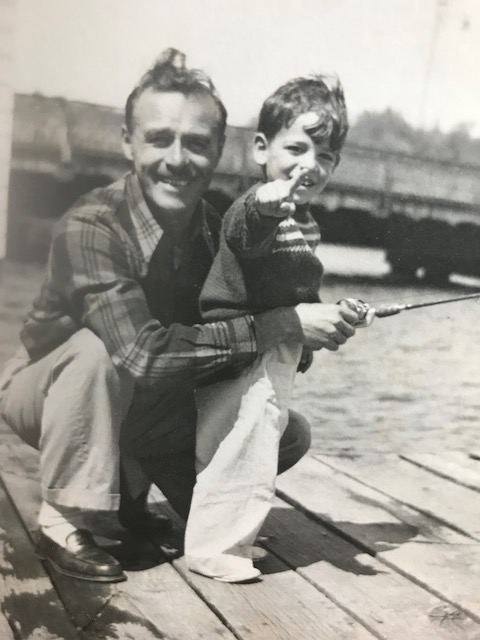

I was ten years old when Uncle Phil came to visit us. I watched him stride up our sidewalk in his crisp, plaid Pendleton shirt,pressed tweed slacks, and smoking a small, honey-colored pipe.

Uncle Phil was a bachelor well into his 50’s. He worked for the family printing company, and he loved nice things – and his bachelorhood gave him both the opportunity and disposable income to get them – clothes, accessories, cars, and best of all, fishing equipment. Uncle Phil was a passionate fly Fisherman.

When Uncle Phil was a young man, he had been a drummer. The story went that he was exceptionally talented, and when he was 14, he had been offered a lucrative job to go on the road and tour with a professional band. But he also suffered from epilepsy, and my grandparents, worried for his well-being, forbade him to travel. I never knew what his level of regret was concerning this, or if it was the epilepsy that kept him from marrying and having children of his own. I do know that he loved his many nephews and nieces, and spending time with them brought him tremendous joy.

Uncle Phil and my mom were the two youngest of nine children. Mom had regaled me with stories of Uncle Phil’s fishing adventures out west, and by the time he was able to pay us a visit, he had attained legendary status in my mind. I was certainly intimidated by all the tales my mom had bestowed on me, and I would sheepishly hang in the background during all the greetings and hugging. But once they were all seated he would turn to me with a wry smile and sparkle in his eye and say, “how’s the fly-tying coming along?” I had been tying for two years at this time, and I would anxiously bring out my fly boxes to show him what I had been working on. And then I would gather up all my nerve and say, “Uncle Phil, did you bring your fly boxes?” At this, he would dig into his canvass and leather overnight bag, and bring out a beautiful Wheatley dry fly box and a mahogany leather wet fly book.

The Wheatley box, when opened, was lined on both sides with little compartments with glass lids that sprung open, revealing dozens of oiled, exquisite dry flies. The wet fly book was filled, page after page, with gorgeous wet fly patterns popular at the time – Montreals, Alexandra’s, Queen of the Waters, Royal Coachmen, Parmachene Bells – all exquisitely tied. There were delicate “over and under” patterns, classic patterns, and also some experimental ties as well.

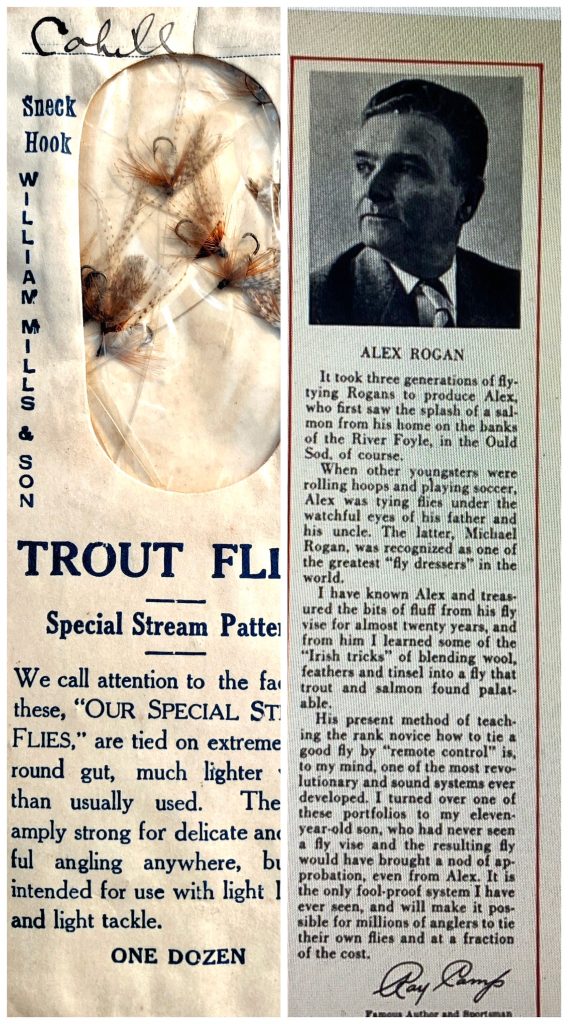

Both the wets and dries were tied by Alex Rogan, who was related to the iconic Rogan family from Ireland – world famous salmon fly tiers. (I believe that Alex was an Uncle of those Irish tiers.) He was a barber by profession, but he also spent time on the staff of Alex Taylor and Son, the fabled fishing shop on 42nd Street in Manhattan where Uncle Phil purchased his fishing equipment and flies.

The Cahills in the package above were hand-tied by William Mills employees in England. Exact dates of creation are unknown, but possibly, given the pattern, hook sizes, gut measurements, etc., the late 1930’s-1950. I believe that during that period, Alex Rogan was here in the US and tying for Mills from his shop. These lovely period-flies were a gift to me from my son, Alex.

Uncle Phil would let me rummage through his boxes and I would pick out a couple of wets and a couple of dries. I would rush them upstairs to my vise and try and copy them to the best of my ability. Just to have these gorgeous patterns on my desk was a thrill! After an hour or so, I would take my copies back downstairs to show Uncle Phil, and he would quietly examine them, while gently offering suggestions – “….see how the tail should be a little longer?” or “look how the hackle should be wound in front of the wings…”. Sixty-five years later, I am still trying to reach the level of perfection of those exquisite Rogan ties. I owe to my Uncle Phil and Alex Rogan (my first influences) my eternal love of the mystery and art of fly-tying and fly fishing.

As he puffed on his pipe, he would relate tales of mornings and evenings spent on Western waters. He would describe the moment a silvered Rainbow exploded on a drifting dry, or when a New Mexican Cutty slammed a swinging wet. Those images struck a match to my imagination that set a fire on my lifelong quest of clear rivers and their inhabitants. They still burn in me as I write this. All of his equipment was vintage and the finest. Beautiful bamboo rods by Leonard and Paine, Hardy reels, newly greased and oiled silk fly lines, and gut leaders that had to be soaked for a day before you could use them. I still remember their looks, feels and the scent of the bamboo, paraffin-oiled lines and leather rod tubes. It was like combing through treasure.

We only fished together once. Two years had passed, and I was twelve. Uncle Phil was a bachelor no more! At 58, he had met and married a school teacher. They drove out to visit us on a bright, blue and gold October day. We drove over to The little Saddle River, a local brook. It was low and slow, and so clear you could be seen a mile away. There were no trout to be found, But it didn’t matter – in my mind I saw those flashes of scarlet and silver and just to be on the water with my Uncle was a thrill.

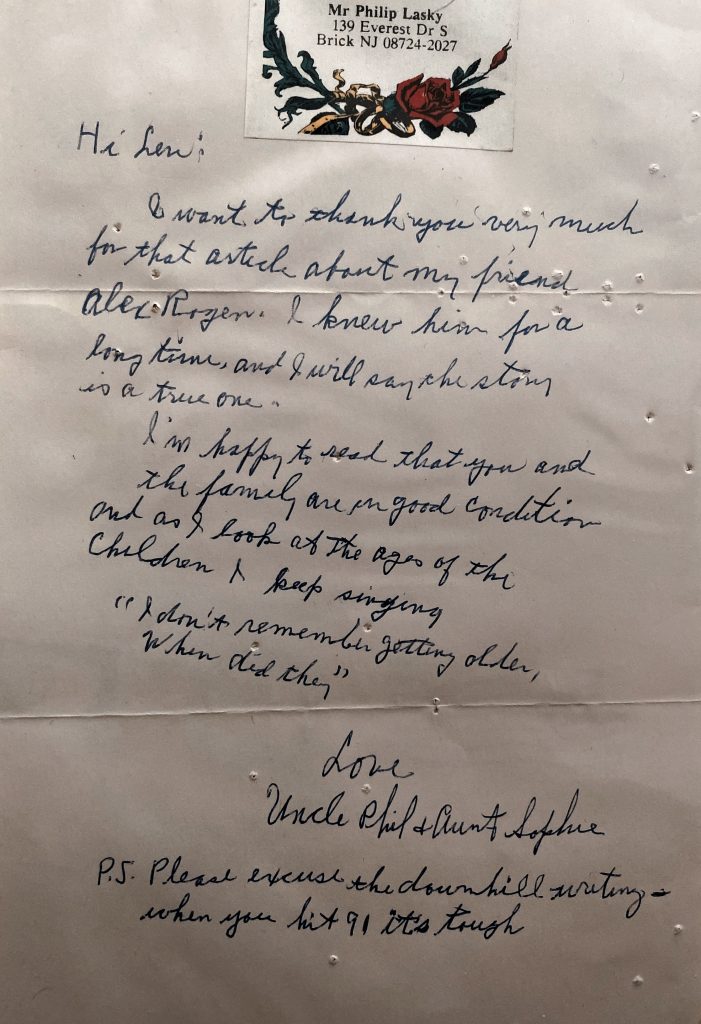

Uncle Phil lived to be 99. Several years before he passed away, I came across an article about the famed Rogan family of fly tiers from Ireland, and put it in an envelope and mailed it out to him. I received a nice response saying how much he had enjoyed the article, and from his personal experience, he believed it to be accurate. I couldn’t help but thinking of how blessed I had been to have had someone in my life at an early age who kindled and encouraged my passion for this incredible pastime. I pray, as I write this, that he is waist-deep in clear, flowing celestial water, throwing sixty feet of oiled C-level silk line into the fray. Thank you, Uncle Phil, and Godspeed.