Cascapedia Grilse

As the summer deepened and the lazy afternoon sun lingered on the tops of the maples and elms, refusing to set, I would rummage through the leaf pile by the old post and rail fence in our backyard. Soon there would be several dozen wigglers safe in the Del Monte corn can, half filled with soil, that my mom was learning to save for my fishing trips. I’d grab my rod and hop on my bike for the short ride down to the brook, several blocks away at the bottom of the hill at the end of the street. It was a small, meandering creek with a sand and mud bottom, and a few stony riffs. Throughout its miles of pools, glides and riffles, it wandered through four towns, and under half a dozen bridges, one of which was the old concrete one on Fairview Avenue at the end of our street. In the swollen coffee-colored early-season water under its abutment, I’d caught my first trout – a twelve-inch brookie, which I proudly ran home with to show my folks. Just above the bridge the brook formed a large pool, curving slowly around to glide smoothly under the bridge. Along one bank of the pool was a sloping grassy bank, a perfect spot to find a good fork-shaped branch, get comfortable, bait up, and see what developed. In addition to the elusive trout, the brook could also surprise a wide-eyed seven year old with catfish, yellow perch, blue gill, eel, roach, suckers and even an occasional bass that had made its way over the spillway at Woodcliff Lake Reservoir five miles upstream. I loved sitting on the bank, still fishing into the big pool above the bridge. When the translucent blue monofilament would twitch, and then slowly the slack would tighten, I never knew what I’d find on the other end. And since most of the put-and-take trout fishermen had long ago stashed their rods in the closet, I generally had the place all to myself.

So I was somewhat surprised, one July evening, as I coasted my Schwinn down the long hill to the bridge with an eight of spades held by a clothes-pin, making a clattering racket in the spokes of the rear wheel. Two figures were already sitting on the bank, my bank, lines dangling in the water.

One of the intruders was an older gentleman – even older, I thought, than my own father. He was short and stocky, his graying hair was thinning, and I could tell he’d be bald someday. He was dressed in rumpled khaki work pants, black shoes, and a white T-shirt, and he looked like he was about a week’s distance from a decent shave. His muscled arm had a colored tattoo just above the biceps, the first that I had ever seen. It was a blue anchor with the words “God Bless America,” circling it, and I imagined that the man must have been in the navy. As I warily approached, the man smiled a warm, genuine smile and puffing on a Lucky Strike said, “Hi, my name is Joe, and this is my son Gary.” Even as a seven-year old, I remembered thinking that there was a hint of sadness in that smile.

I soon learned that Joe worked for the town as a sanitation man, and lived in a house two blocks from the brook. Later, when I rode past the house on my bike, I discovered that Joe also seemed to collect and sell junk parts of almost anything and everything. Stacks of doors, tires, old swing sets, hubcaps, shingles – you name it, were piled up in every nook and cranny in the front yard. The small house was of weathered, whitish stucco with a red clay shingled roof. There was nothing remarkable about it, nothing that stood out or caught my eye. Just a little, nondescript house among many nondescript houses.

It was difficult to tell how old Gary was. Gary had Down’s Syndrome, but back then, I had heard my parents, their voices lowered, refer to people such as Gary as “retarded.” Not knowing how to interpret that, or how someone actually came to be “retarded,” my natural seven-year old reserve led me to keep my distance. I knew that there was a class in school called the “special class” that contained other children like Gary. But they were completely segregated from the everyday goings-on of the school, an unfortunate trait of 1950’s educational philosophy. While this was never talked about, its damaging subtlety was not lost on me, and the silent assumption drawn was that one did not associate with these children. Consequently, I felt ill at ease around them. So setting up my tackle, I kept a wary eye on Gary. But I soon learned that keeping my distance from him was a horse of a different color.

Gary sat next to his father on the bank, wide-eyed and bushy-tailed, a non-stop stream of chatter. What kind of fish were in the water? Were they big fish? Where was the line? And on and on he went, and when he had seemingly exhausted every conceivable question, he’d just begin all over again as if he’d never asked them in the first place. And to make matters worse for me, who loved the solitude of the pool, Gary seemed to have no inhibitions about wanting to get to know me. With an almost unconfined energy, he immediately sat down next to me and began asking me the same questions. Petrified, and unsure of how to react, I stammered for answers. But Joe just chuckled quietly, and with kind eyes said, “Gary, come here and I’ll show you where the fish are.” Gary bolted back over, and with infinite patience Joe began the explanations once again, the two veiled in a fog of bluish smoke from Joe’s Lucky Strikes.

I felt a small tug on my line, and tensed slightly. A second bump, then another, and I lifted the tip sharply. A minute later I had a fat yellow perch flopping on the bank. Gary was wild with excitement. “Mine!” he yelled at the top of his lungs, running over to me. I began to unhook the wiggling fish. “Mine,” Gary again yelled. Joe walked over and took Gary’s hand. “The fish belongs to the boy, Gary – he’s the one who caught it.” I held the fish momentarily and threw it gently back into the pool. Gary pointed at the water yelling, “fish, fish.” Joe laughed and said “C’mon Gary, let’s try to catch that fish all over again.” Gary sat back down next to Joe, still pointing at the water and saying “fish,” and glancing back at me.

The entire length of the pool was now in shadow, and the western sky was washed with orange. I swatted at a mosquito, and the trees were a chorus of locusts and crickets.

We had been sitting there over two hours now, making small talk about fishing, baseball, school and whatnot. I was beginning to feel more at ease, and it seemed to me that Gary had calmed down a bit too, although he continued to pepper Joe with questions. As twilight faded to night, I gathered my things and said goodbye. Joe said, “It was nice meeting you Len – maybe we’ll see you here again.” As I peddled my bike across the bridge, out of the corner of my eye I saw Gary and Joe waving. They sat and watched me wave back, the rat-tat-tat clatter of the card in the spokes gradually fading in the spreading darkness.

I leaned the bike against the wall inside the old garage behind our house. The garage was more like a barn, with a loft and roughly-cut exposed oak beams everywhere. It had been built around the turn of the century, along with the house. It still had some ancient, rusting lawn equipment hanging from nails in the wall, and about a dozen old license plates, some going back to the 1920’s, nailed here and there to the beams. My dad had discovered a family of bats living in the rafters, and I had been there when they had been removed. I had never actually seen one close up before. Black, rubber-like skin, pointed ears, pterodactyl-like wings. I thought they were cool.

I slipped through the squeaky screen door in the back of the old house. I rested my rod in a nook by the door, next to the line of jackets hanging from brass coat hooks. I could hear my mom working in the kitchen, humming a familiar tune. She looked up and smiled as I entered the kitchen. “Any luck?” I nodded and said, “Yeah, I got a few – there was this old guy and his son.” “Anyone we know?” “Er, na, I don’t think so. Say mom, how does someone get to be retarded?” My mother put down the plate she was holding, and looked at me. The question had taken her by surprise. Boys, she thought. Who can figure out what they’re thinking? She lifted the yellow-checkered apron she had been wearing, over her head, untying the strings in the back. “Well,” she began, “it usually is from something that happens before someone is even born. Something goes wrong while a baby is still inside its mother. Why do you ask, Len?” “Aw, I wuz just wonderin’.” I wasn’t about to mention my new acquaintances, and she did not press me. She had come to expect these veiled references, and had learned to be patient. She usually got the whole story in time. I had taken a step towards the stairs when she said, “I baked an apple cobbler Len, would you like some?”

I sat in my room, a dish of apple cobbler on my night table. It was still warm, and heavy with brown sugar and cinnamon. I finished the last of it. A breeze had come up, and the lacy curtains on either side of the big, open windows fluttered inwards like flags. The humidity had built up steadily during the day, and the cooling breeze felt great. I lay back on my bed. The dull rumble of distant thunder echoed in the backyard. I wondered where the storm was, and how long it would be before it got here. I thought about Joe and Gary, and what my mother had said. I wondered if Gary understood that he was different from the other kids. Gradually, my eyelids grew heavy. More tired than I realized, I was picturing the way my line slowly tightened as an unseen shadow grabbed the bait somewhere deep in the pool above the bridge. Lost in sleep, I never saw the sky light up with the approaching storm, or felt the first drops of rain through the big, screened window.

The long, seemingly endless days of a seven year old’s summer meandered through the 1950’s calendar, slow as molasses, and with reassuring consistency. I was running into Joe and Gary regularly in the evenings by the pool above the bridge. Joe was a never-ending source of patience and kindness. No matter how many times Gary would ask the same question or attempt the same task, Joe would quietly tell or show him the answer. Tonight, looking back, I thought about my own children, intelligent and curious. And at the many times over the years I had become impatient helping them with homework, or teaching them some complicated task. I shook my head remembering, and it made me even more in awe of Joe’s patience and devotion.

As the summer rolled along, I had begun to understand Gary a little more, becoming more able to interpret his mannerisms and moods. I was beginning to see him as a distinct personality rather than a disabled person. Gary was like a ray of sunshine, always curious, always excited, and it didn’t bother me anymore when Gary would sit down right next to me and begin his non-stop questions. I would try to answer as best I could, or look to Joe for help. Sometimes I’d watch the two out of the corner of my eye, wondering if Joe worried about Gary’s future, and it made me sad to think that Gary would never have the opportunities that many other children would.

September arrived, but the humidity of the east-coast dog days hung on. One evening as the three of us sat on the bank hoping for a wisp of a breeze, three class bullies from my school rode across the bridge on their bikes. A few days later, my friend Larry and I were playing ball in the school yard when the same three approached us. “Hey Handler, saw ya fishin’ with garbage man Joe and his dumb kid.” I flushed. The sadness I felt was for Joe and Gary. And for the ignorant intolerance from the bully that stood before me. But I had seen it once before.

The leader of the pack was named Jackie Bedford. Earlier in the year I had been in school, standing in line at the water fountain, waiting my turn to have a drink.

I had just leaned down to take a sip, when out of nowhere, Jackie had shoved me aside, snarling “Get out of the way ya dirty Jew.” I flushed. It had never crossed my mind up to then that a person’s religion could be subject to ridicule. I stood there dumbfounded. My friend Fred had been standing there, and intervened, “ Aw, he’s all right, he’s a good Jew.” Although well intended, I instinctively knew that the defense had badly missed the mark. Later that night, when I told my parents what Jackie had said, my father had quietly replied, “Len, when you hear a child say something like that, what you’re really hearing is their parents speaking.” I had never forgotten those words.

Larry and I stood in the school yard facing the three bullies. I was much bigger than Jackie, and Larry was tougher than all of them together. I knew that Jackie was not about to push us too far. So I looked Jackie in the eye and said defiantly, “Yeah, want to make something of it?” Jackie wasn’t about to risk the embarrassment of losing a fight. He mumbled something about “dummies,” turned, and walked away, the group issuing a steady stream of insults and laughter on lowered voices. I was relieved that we didn’t have to fight, my heart still pounding. But I walked from the playground that day with the hollow feeling of ignorance and intolerance. It was a feeling that would surface again and again as I grew older.

The maples and elms began to show their first blush of yellows and oranges. The shadows seemed to lengthen faster and earlier across the pool, and the crisp, colorful oak leaves spun around in the brook’s current like little sailboats. My mom had taken me out for the fall ritual of buying school clothes, which I suffered through with great distress. I had continued to meet Joe and Gary throughout the summer. Tonight, sitting at my cluttered desk, our lazy Beagle, Tucker, sound asleep at my feet, fighting my own graying hair, I pictured those long ago evenings. They were the last time I saw my two fishing companions. The following spring I had heard a rumor that Joe had suffered a heart attack and had passed away. I did not know if it was true, though afterward, I drove past their house and it looked abandoned, the yard still cluttered with rusting junk. I never knew what became of Gary. And for the life of me, I could not remember if the last time we had been together, I had even said “goodbye.”

Though the bigotry and intolerance I encountered in my seventh year haunt me to this day, I discovered in retrospect that I was blessed to witness, at an early age, that real love has no boundaries. I never forgot the unending patience and compassion that Joe unconditionally gave to Gary. And I learned how much it can hurt to be cruelly labeled as “different.” They were lessons that remained with me for the rest of my life.

A great morning with the Grandkids and guide Ben Burdine fishing for Stripers on LI Sound. Both Lee and Ben landed fish exceeding 15 pounds.

There’s a famous cliché about the freckle-faced kid with the cane pole who meets the grizzled, wise old fly fisherman. H.T. Webster, cartoonist supreme, touched on the subject on a number of occasions in a series of fishing cartoons he entitled “The Thrill that Comes Once In a Lifetime.” In them, the cagey old dry-fly veteran, skunked after a frustrating day on the river, runs into the local, freckled-face kid along the riverbank. The kid is holding a can of worms, a cane pole and a huge, hook-jawed lunker, horsed in that very afternoon. Chomping his lip in envy, the grizzled old pro stands there red-faced as the kid offers him his can of worms, or even worse, a self-tied fly pattern he created for the river from the hair of his hound dog. The message is clear – that on the river, all bets are off. And so it was with me the year I turned twelve.

School was out for the summer when my parents joined the swim club. The club had been built on several hundred acres of land that had once surrounded a spring-fed brook. Sometime back in the 1930’s, the brook had been dammed to form a long, weedy, lake. That lake became the central body of water around which the club was developed. The lower outlet of the lake was dammed and redirected, and from that flow, a second, sand-bottom swimming lake was created. At the head of the big lake, what was left of the original brook disappeared into a dense, brushy swamp.

The lake was heavily stocked with largemouth bass and a few hundred brown trout. The browns lasted for a couple of seasons, hanging deep, hugging the springs where they sucked the cool water through their gills. But the combination of the weedy lake, high water temperatures, and hungry, aggressive bass took their inevitable toll, and it had been years since anyone had seen a trout in Darlington Lake. However, it was teeming with big bass, perch, bullheads, and bluegill big as salad plates.

On summer weekdays, my sister Carole and I would hop in the car with mom, and we’d all drive up to the club. We would unload the lawn chairs and towels, Coppertone, and picnic basket from our green-and-white ’56 Buick, and I would help set them up in the grassy area by the swimming pool. Carole would swim, and mom would socialize with her friends and acquaintances. And I would grab my fishing gear and head for the upper lake, not to be seen again until the afternoon shadows had lengthened and I had waited until the last possible moment to reel in and trudge back to the car.

Just to the north of the club, on a patch of land along the county road, stood an old white clapboard house with a long, sagging front porch. It had been there since the turn of the last century, a true antique. There were flowers growing in the flower boxes in front of the two nondescript ground floor windows, and smoke could be seen drifting from the old fieldstone chimney. At the side, a rose trellis leaned against the storm cellar door of gray painted wood slats. The short driveway in front was covered with marble-sized gravel, and parked on it was an ancient maroon Pontiac. And inside the house, I soon learned, lived the grizzled old fly fisherman.

Bill Swin had grown up in a simpler time. He had spent his life hunting rabbit, quail, duck, pheasant, squirrel and deer, and fishing for trout in a then- rural New Jersey. At fifty-eight, he looked more like eighty. Teeth missing, ruddy, gnarled complexion, with scraggly silver shoulder-length hair, he had a large bulbous nose, more probably from the years of homemade brew that he made and swizzled weekly than from his rugged self-subsistence. He wore a rumpled flannel shirt and baggy worsted trousers, worn shiny, several sizes too large, and held up by a by an ancient, leather belt.

The founders of the club had instituted strict rules concerning trespassing, forbidding non-members from utilizing club property for recreation. So Bill was forbidden to fish and hunt on club land. But he had been doing just that since he had first held a fishing rod. “After all, I wuz here first,” he’d later tell me. And the club officials soon learned that, no matter what and how they tried, Bill would not be deterred. His poaching became so legendary that finally the club did the only thing it could. They hired him as a handyman and extended fishing privileges to him. And soon the grizzled old fisherman, standing on the bank making long, sweeping backcasts with his fly rod became a common sight. The club learned that it paid them an unexpected dividend. Members who loved to fish began asking Bill’s advice, and soon, to no credit of its own, the club boasted of its own fishing pro.

I watched, from a distance, as Will laid out sixty feet of fly line. I saw the rod tip come back, then shoot forward in the first roll cast I had ever seen. The dark green silk fly line looped forward until the stiff, knotted tapered leader turned over and straightened, and the little popper landed with a plunk. The circle of ripples slowly radiated outward until the water’s surface was again like a mirror. I saw the little popper plunk once more, then suddenly disappear in a bulging swirl and sharp smack. Bill’s rod arched, and I was hooked deeper than the fat bass.

I had already been tying flies for several years, and although I wasn’t about to break any fly casting records, in a pinch I could bully some moderate distance out of my heavy three-piece bamboo. But the red Shakespeare fly reel was loaded with shiny green G-level fly line, far too light for that telephone pole of a rod. I stood on the bank, awkwardly false-casting over the bluegill beds that filled the shallow water by the lower spillway. Suddenly, from behind, I heard a soft, nasal voice. “Listen here, fella, don’t drop that rod on your backcast, keep your arm closer to your side – say, what weight line are ya using anyway?” And thus began a thirty year friendship with the most unforgettable character I have ever met.

Bill taught to me about matching line weights with rods. He worked with me on the basic aspects of fly casting. And by the end of July, I was shooting my new C-level Cortland line out like a pro. But the lessons did not come cheaply. One day, when I was changing flies, Bill eyeballed my fly box with great interest. “Where’d ya get all those flies?” I told Bill that I had tied them all myself. Soon, Bill was telling me, “so why don’tcha tie me up a bunch of those white bucktails for next week – a dozen or so ought to do it.” And eager to please him, and proud the old man liked my flies enough to use, I would spend the next couple of evenings at my vise. Before long we were inseparable, fishing together whenever Bill was off work. We would stand on the bank beside the long footbridge over the spillway that separated the upper lake from the swimming lake and catch fat bluegill, one after the other, on tiny wet and dry flies. Bathers from the pool would walk over and gather on the footbridge to watch us cast, a collective aah going up from the crowd every time another chunky bluegill would nail the fly. I secretly loved the audience.

One day Bill said “C’mon Lenny (he pronounced it “Lainy”), let’s fish above.” We hiked the perimeter of the lake, through the groves of red pine, the ground spongy with moss and thick with the brittle, browned needles, an occasional mushroom forcing its way through the interlaced layers. We reached the upper cove where the old brook emptied into the lake. The woods above were swampy and thick with brush, and looked impenetrable. I had taken a few furtive looks, but had never mustered the nerve to explore this intimidating stretch of water by myself. Bill circled around the brush, and as I followed, carefully avoiding the vines and brambles that hung from all directions, we came upon a partially-hidden path that I had never noticed from the cove. In a minute or two, the brush had cleared, and we were standing in front of a large, tea-colored pool. Above the pool, the creek was narrow and had carved deeply into the far, undercut bank. Willows and every conceivable type of bramble and shrub grew to the water’s edge. The pool and glide above it had depth, and I could not see much below the surface. The thick growth of white oak, spruce, poplar and pine suffocated the afternoon sun. The air was still, any breeze stifled by the heavy canopy of foliage. I swatted at a mosquito.

“Lay one over there,” Bill whispered, pointing to a gnarled root protruding from the opposite bank. I still had the little Leadwing Coachman wet I had been working over the bluegill at the spillway. The wings had been pretty thoroughly chewed, with not much more than a wisp of grayish-brown duck quill remaining. I rolled the fly across, and began to slowly mend in my line. There was a sudden sharp tug, and I felt the rod pulse and vibrate. In a minute, I had the fish on shore, a ten-inch native brookie – the first that I had ever seen. Together, we crouched down for a better look. Dark olive along the back blended into sides of metallic blue-green. Red, yellow and black spots ran down the lateral line. The belly was a deep burnt orange with grayish-black streaks, fading to pure white along the ventral fins. The fins were streaked along the edges with orange, black and white. It was the prettiest fish I had ever seen.

We left the creek that afternoon with four lovely brookies. But the best surprise came later that evening, when my mom broiled them. The deep reddish-orange flesh was exquisite, and for years afterward, mom talked about how delicious those trout were. But even back then, native trout were a precious commodity, and Bill and I kept that secret between us through all my childhood. We fished the little creek until I graduated from high school and went away to college. I loved those brookies and the hidden, little cove. Years later, on a visit back, I was saddened to discover that the club had been purchased by the county and turned into a park. The upper woods had been bulldozed and cleared, both for mosquito control and to make room for athletic fields, and the brook had been straightened. I stood on a manicured bank of sod, staring out at the sterile, straight creek. I shook my head at all the memories lost along the downed trees and missing landmarks. And at the county government that had no idea of the precious natural resource that they had destroyed, and that was forever lost.

One humid day in August, we had worked around the perimeter of the lake, shooting poppers to the edge of the lily pads and weed beds. It was ninety degrees in the shade, the chorus of locusts taking turns buzzing their long, mournful drones. Not a leaf rustled in the thick canopy of oak and maple above us. I imagined that every bass must be pinned to the cool, deep springs that fed the lake. So we plopped down on the mossy bank to rest our tired legs and casting arms. I sipped tepid water from my canteen. I loved to hear Bill tell fish stories, of which he seemed to have an endless supply. But through the years, I noticed that they all began the same way. “Well, I’ll tell ya Lainy,” Bill would say, “I wuz down on the East Branch, and there was a tremendous hatch. I wuz floatin’ a number 12 Cahill through that big hole above the bridge, when loom – out of nowhere he came…” (Loom was Bill’s favorite descriptive action word, and he always elongated and emphasized the oo.) And on it would go. We rested and told tales awhile, when Bill said, “Lainy, do you ever go fishin’ with your dad?” I loved my dad very much, but he did not share my passion for fishing. I thought for a moment and said “not too much, but we like to play baseball together. Bill quietly nodded, but for the first time, it occurred to me how lonely living in the old house by himself must be. I smiled shyly and Bill chuckled, got up, and said, “Well, let’s catch us a bass.”

One morning, after several hours of casting along the lily pads, Bill said “C’mon, Lainy, let’s have some lunch back at my house.” It was the first time I had ever been inside Bill’s house. As we walked through the creaky screen door into the kitchen, I was amazed to see a sink made of charcoal gray slate slabs, with a long, curving handled water pump. A large green and white porcelain wash bowl sat on the wood counter to the right, and I realized with a shock that there was no indoor plumbing. The two rooms downstairs were filled with vintage oak furniture. In summers to come, we would sit on Bill’s front porch and sip lemonade, while I tied flies for both of us on my field vise. Occasionally a car would pull up on the gravel driveway, and a person in a business suit or dress would get out and approach the porch wearing a pasted-on smile and affecting a practiced air of friendliness. Bill would eye them with utter disdain, and dismiss them summarily, usually with a gruff “Ain’t no need for you to hang around here” or “Why don’t you just go about your business?” When I finally got up the nerve to ask Bill who they were, he growled “antique dealers waitin’ for me to die.”

Bill and I remained close friends as I grew into my teens, although the demands of school, activities and girls weighed heavily on me. In the blink of an eye I was off to college, married, and immersed in a family and career. But every summer, if I could, I’d stop back, usually in July, to visit the old man and spend a few hours on the lake with him. But, as so often happens, the stretches between visits grew longer and longer. My hair was peppered now with silver, and on my way to the office one morning, I realized it had been thirty-five years since that first meeting by the bluegill beds. We had corresponded infrequently, and one early December morning, I sat down and wrote Bill a long letter, enclosed it in a Christmas card, and mailed it off. Several months went by without a response. Finally, in March, a note arrived from Bill’s sister Claire. It was a short, rather formal note, saying that Bill had passed away.

I felt a quiet, deep sadness. Our friendship had been a wonderful and important part of my childhood, and I had learned so much from the old man. Not knowing what else to do, I wrote a eulogy for Bill, and sent it off to the outdoor editor of the local newspaper in his hometown. A few weeks later, I received a heartfelt note from Claire. The note ended, “Bill’s life was fishing and hunting the woods and rivers where he grew up, and he loved doing it with you.” I took a deep breath, and for a moment, we were back on the bank by the footbridge, our long sweeping casts unfurling towards the bluegill beds.

Just then, my nine-year old son Aaron burst into the room. I put the note down. Aaron looked at it and asked, “What’s that, daddy?” I smiled and said softly, “A note about a very old, dear friend who caught lots of big fish. Come here, Aaron, and I’ll tell you all about him.”

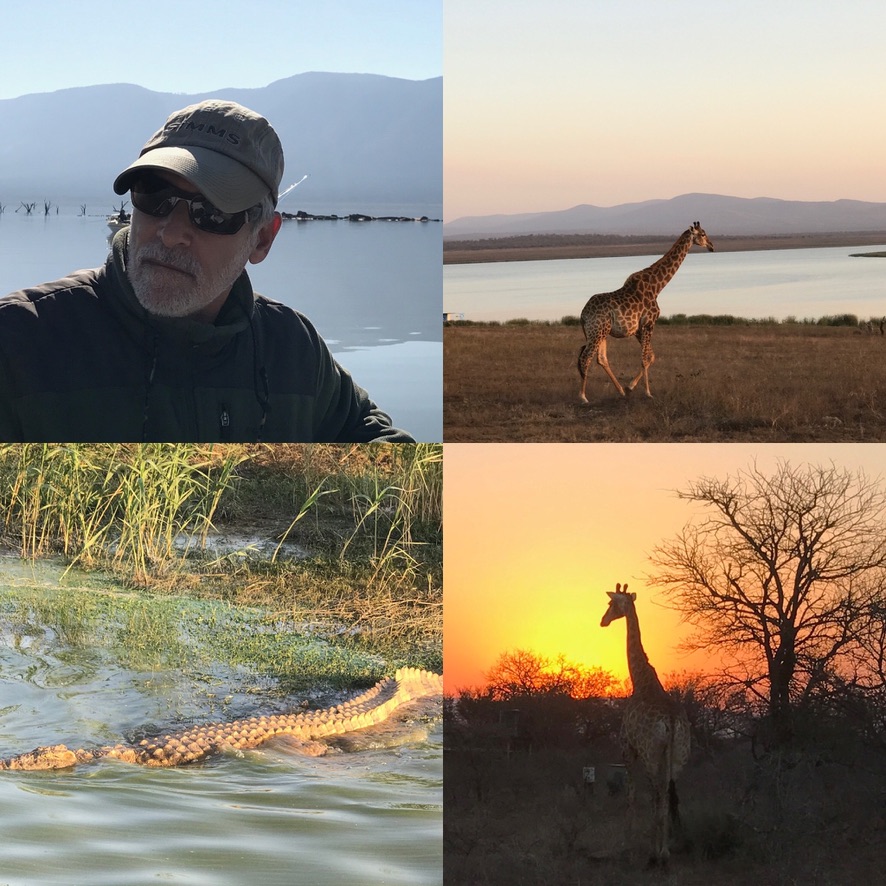

Pongola, South Africa; Looking for Tiger Fish;

Big Brown at “The Wall” at Buckingham; (Main Stem)

Above Tower Road;