There’s a famous cliché about the freckle-faced kid with the cane pole who meets the grizzled, wise old fly fisherman. H.T. Webster, cartoonist supreme, touched on the subject on a number of occasions in a series of fishing cartoons he entitled “The Thrill that Comes Once In a Lifetime.” In them, the cagey old dry-fly veteran, skunked after a frustrating day on the river, runs into the local, freckled-face kid along the riverbank. The kid is holding a can of worms, a cane pole and a huge, hook-jawed lunker, horsed in that very afternoon. Chomping his lip in envy, the grizzled old pro stands there red-faced as the kid offers him his can of worms, or even worse, a self-tied fly pattern he created for the river from the hair of his hound dog. The message is clear – that on the river, all bets are off. And so it was with me the year I turned twelve.

School was out for the summer when my parents joined the swim club. The club had been built on several hundred acres of land that had once surrounded a spring-fed brook. Sometime back in the 1930’s, the brook had been dammed to form a long, weedy, lake. That lake became the central body of water around which the club was developed. The lower outlet of the lake was dammed and redirected, and from that flow, a second, sand-bottom swimming lake was created. At the head of the big lake, what was left of the original brook disappeared into a dense, brushy swamp.

The lake was heavily stocked with largemouth bass and a few hundred brown trout. The browns lasted for a couple of seasons, hanging deep, hugging the springs where they sucked the cool water through their gills. But the combination of the weedy lake, high water temperatures, and hungry, aggressive bass took their inevitable toll, and it had been years since anyone had seen a trout in Darlington Lake. However, it was teeming with big bass, perch, bullheads, and bluegill big as salad plates.

On summer weekdays, my sister Carole and I would hop in the car with mom, and we’d all drive up to the club. We would unload the lawn chairs and towels, Coppertone, and picnic basket from our green-and-white ’56 Buick, and I would help set them up in the grassy area by the swimming pool. Carole would swim, and mom would socialize with her friends and acquaintances. And I would grab my fishing gear and head for the upper lake, not to be seen again until the afternoon shadows had lengthened and I had waited until the last possible moment to reel in and trudge back to the car.

Just to the north of the club, on a patch of land along the county road, stood an old white clapboard house with a long, sagging front porch. It had been there since the turn of the last century, a true antique. There were flowers growing in the flower boxes in front of the two nondescript ground floor windows, and smoke could be seen drifting from the old fieldstone chimney. At the side, a rose trellis leaned against the storm cellar door of gray painted wood slats. The short driveway in front was covered with marble-sized gravel, and parked on it was an ancient maroon Pontiac. And inside the house, I soon learned, lived the grizzled old fly fisherman.

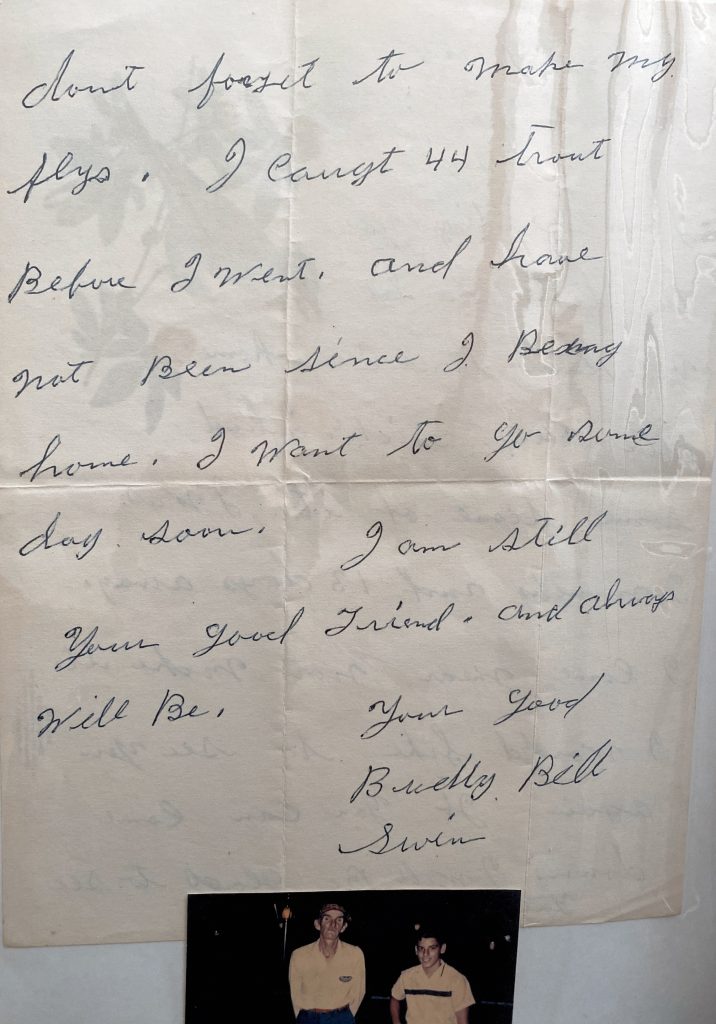

Bill Swin had grown up in a simpler time. He had spent his life hunting rabbit, quail, duck, pheasant, squirrel and deer, and fishing for trout in a then- rural New Jersey. At fifty-eight, he looked more like eighty. Teeth missing, ruddy, gnarled complexion, with scraggly silver shoulder-length hair, he had a large bulbous nose, more probably from the years of homemade brew that he made and swizzled weekly than from his rugged self-subsistence. He wore a rumpled flannel shirt and baggy worsted trousers, worn shiny, several sizes too large, and held up by a by an ancient, leather belt.

The founders of the club had instituted strict rules concerning trespassing, forbidding non-members from utilizing club property for recreation. So Bill was forbidden to fish and hunt on club land. But he had been doing just that since he had first held a fishing rod. “After all, I wuz here first,” he’d later tell me. And the club officials soon learned that, no matter what and how they tried, Bill would not be deterred. His poaching became so legendary that finally the club did the only thing it could. They hired him as a handyman and extended fishing privileges to him. And soon the grizzled old fisherman, standing on the bank making long, sweeping backcasts with his fly rod became a common sight. The club learned that it paid them an unexpected dividend. Members who loved to fish began asking Bill’s advice, and soon, to no credit of its own, the club boasted of its own fishing pro.

I watched, from a distance, as Will laid out sixty feet of fly line. I saw the rod tip come back, then shoot forward in the first roll cast I had ever seen. The dark green silk fly line looped forward until the stiff, knotted tapered leader turned over and straightened, and the little popper landed with a plunk. The circle of ripples slowly radiated outward until the water’s surface was again like a mirror. I saw the little popper plunk once more, then suddenly disappear in a bulging swirl and sharp smack. Bill’s rod arched, and I was hooked deeper than the fat bass.

I had already been tying flies for several years, and although I wasn’t about to break any fly casting records, in a pinch I could bully some moderate distance out of my heavy three-piece bamboo. But the red Shakespeare fly reel was loaded with shiny green G-level fly line, far too light for that telephone pole of a rod. I stood on the bank, awkwardly false-casting over the bluegill beds that filled the shallow water by the lower spillway. Suddenly, from behind, I heard a soft, nasal voice. “Listen here, fella, don’t drop that rod on your backcast, keep your arm closer to your side – say, what weight line are ya using anyway?” And thus began a thirty year friendship with the most unforgettable character I have ever met.

Bill taught to me about matching line weights with rods. He worked with me on the basic aspects of fly casting. And by the end of July, I was shooting my new C-level Cortland line out like a pro. But the lessons did not come cheaply. One day, when I was changing flies, Bill eyeballed my fly box with great interest. “Where’d ya get all those flies?” I told Bill that I had tied them all myself. Soon, Bill was telling me, “so why don’tcha tie me up a bunch of those white bucktails for next week – a dozen or so ought to do it.” And eager to please him, and proud the old man liked my flies enough to use, I would spend the next couple of evenings at my vise. Before long we were inseparable, fishing together whenever Bill was off work. We would stand on the bank beside the long footbridge over the spillway that separated the upper lake from the swimming lake and catch fat bluegill, one after the other, on tiny wet and dry flies. Bathers from the pool would walk over and gather on the footbridge to watch us cast, a collective aah going up from the crowd every time another chunky bluegill would nail the fly. I secretly loved the audience.

One day Bill said “C’mon Lenny (he pronounced it “Lainy”), let’s fish above.” We hiked the perimeter of the lake, through the groves of red pine, the ground spongy with moss and thick with the brittle, browned needles, an occasional mushroom forcing its way through the interlaced layers. We reached the upper cove where the old brook emptied into the lake. The woods above were swampy and thick with brush, and looked impenetrable. I had taken a few furtive looks, but had never mustered the nerve to explore this intimidating stretch of water by myself. Bill circled around the brush, and as I followed, carefully avoiding the vines and brambles that hung from all directions, we came upon a partially-hidden path that I had never noticed from the cove. In a minute or two, the brush had cleared, and we were standing in front of a large, tea-colored pool. Above the pool, the creek was narrow and had carved deeply into the far, undercut bank. Willows and every conceivable type of bramble and shrub grew to the water’s edge. The pool and glide above it had depth, and I could not see much below the surface. The thick growth of white oak, spruce, poplar and pine suffocated the afternoon sun. The air was still, any breeze stifled by the heavy canopy of foliage. I swatted at a mosquito.

“Lay one over there,” Bill whispered, pointing to a gnarled root protruding from the opposite bank. I still had the little Leadwing Coachman wet I had been working over the bluegill at the spillway. The wings had been pretty thoroughly chewed, with not much more than a wisp of grayish-brown duck quill remaining. I rolled the fly across, and began to slowly mend in my line. There was a sudden sharp tug, and I felt the rod pulse and vibrate. In a minute, I had the fish on shore, a ten-inch native brookie – the first that I had ever seen. Together, we crouched down for a better look. Dark olive along the back blended into sides of metallic blue-green. Red, yellow and black spots ran down the lateral line. The belly was a deep burnt orange with grayish-black streaks, fading to pure white along the ventral fins. The fins were streaked along the edges with orange, black and white. It was the prettiest fish I had ever seen.

We left the creek that afternoon with four lovely brookies. But the best surprise came later that evening, when my mom broiled them. The deep reddish-orange flesh was exquisite, and for years afterward, mom talked about how delicious those trout were. But even back then, native trout were a precious commodity, and Bill and I kept that secret between us through all my childhood. We fished the little creek until I graduated from high school and went away to college. I loved those brookies and the hidden, little cove. Years later, on a visit back, I was saddened to discover that the club had been purchased by the county and turned into a park. The upper woods had been bulldozed and cleared, both for mosquito control and to make room for athletic fields, and the brook had been straightened. I stood on a manicured bank of sod, staring out at the sterile, straight creek. I shook my head at all the memories lost along the downed trees and missing landmarks. And at the county government that had no idea of the precious natural resource that they had destroyed, and that was forever lost.

One humid day in August, we had worked around the perimeter of the lake, shooting poppers to the edge of the lily pads and weed beds. It was ninety degrees in the shade, the chorus of locusts taking turns buzzing their long, mournful drones. Not a leaf rustled in the thick canopy of oak and maple above us. I imagined that every bass must be pinned to the cool, deep springs that fed the lake. So we plopped down on the mossy bank to rest our tired legs and casting arms. I sipped tepid water from my canteen. I loved to hear Bill tell fish stories, of which he seemed to have an endless supply. But through the years, I noticed that they all began the same way. “Well, I’ll tell ya Lainy,” Bill would say, “I wuz down on the East Branch, and there was a tremendous hatch. I wuz floatin’ a number 12 Cahill through that big hole above the bridge, when loom – out of nowhere he came…” (Loom was Bill’s favorite descriptive action word, and he always elongated and emphasized the oo.) And on it would go. We rested and told tales awhile, when Bill said, “Lainy, do you ever go fishin’ with your dad?” I loved my dad very much, but he did not share my passion for fishing. I thought for a moment and said “not too much, but we like to play baseball together. Bill quietly nodded, but for the first time, it occurred to me how lonely living in the old house by himself must be. I smiled shyly and Bill chuckled, got up, and said, “Well, let’s catch us a bass.”

One morning, after several hours of casting along the lily pads, Bill said “C’mon, Lainy, let’s have some lunch back at my house.” It was the first time I had ever been inside Bill’s house. As we walked through the creaky screen door into the kitchen, I was amazed to see a sink made of charcoal gray slate slabs, with a long, curving handled water pump. A large green and white porcelain wash bowl sat on the wood counter to the right, and I realized with a shock that there was no indoor plumbing. The two rooms downstairs were filled with vintage oak furniture. In summers to come, we would sit on Bill’s front porch and sip lemonade, while I tied flies for both of us on my field vise. Occasionally a car would pull up on the gravel driveway, and a person in a business suit or dress would get out and approach the porch wearing a pasted-on smile and affecting a practiced air of friendliness. Bill would eye them with utter disdain, and dismiss them summarily, usually with a gruff “Ain’t no need for you to hang around here” or “Why don’t you just go about your business?” When I finally got up the nerve to ask Bill who they were, he growled “antique dealers waitin’ for me to die.”

Bill and I remained close friends as I grew into my teens, although the demands of school, activities and girls weighed heavily on me. In the blink of an eye I was off to college, married, and immersed in a family and career. But every summer, if I could, I’d stop back, usually in July, to visit the old man and spend a few hours on the lake with him. But, as so often happens, the stretches between visits grew longer and longer. My hair was peppered now with silver, and on my way to the office one morning, I realized it had been thirty-five years since that first meeting by the bluegill beds. We had corresponded infrequently, and one early December morning, I sat down and wrote Bill a long letter, enclosed it in a Christmas card, and mailed it off. Several months went by without a response. Finally, in March, a note arrived from Bill’s sister Claire. It was a short, rather formal note, saying that Bill had passed away.

I felt a quiet, deep sadness. Our friendship had been a wonderful and important part of my childhood, and I had learned so much from the old man. Not knowing what else to do, I wrote a eulogy for Bill, and sent it off to the outdoor editor of the local newspaper in his hometown. A few weeks later, I received a heartfelt note from Claire. The note ended, “Bill’s life was fishing and hunting the woods and rivers where he grew up, and he loved doing it with you.” I took a deep breath, and for a moment, we were back on the bank by the footbridge, our long sweeping casts unfurling towards the bluegill beds.

Just then, my nine-year old son Aaron burst into the room. I put the note down. Aaron looked at it and asked, “What’s that, daddy?” I smiled and said softly, “A note about a very old, dear friend who caught lots of big fish. Come here, Aaron, and I’ll tell you all about him.”